ANOTHER PLANET ON EARTH: JAPAN

見ぬが花

Literal Translation: Not seeing is a flower

Meaning: Reality can't compete with imagination

出る杭は打たれる

Literal Translation: The nail that sticks out gets hammered down

Meaning: Being different can lead to criticism or punishment. Conformity is considered a more accepted path

Read those proverbs again. Slowly and thoughtfully. It's the closest attempt to capture the elusive essence of the Japanese culture. Temporality, fluidity, and escapism, combined with an adamant sense of duty, are the key elements of people's world perception living on this one-of-a-kind island.

I still can't believe that I saw Japan with my own eyes and lived through 10 days of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Nara. That experience outstretched my perspective on life like no other travel adventure.

Sorry for that pondering and airy-fairy tone, but Japan is just like that! It makes you slow down with a gentle invitation to sit down and fix your gaze on everything that surrounds you. I want to share everything I can about this un-Earthly country and persuade you to go experience it for yourselves!

The Japanese culture is so distinctivethat it's nearly impossible to mistake it for any other. Sushi, kimono, sakura, anime, and Fuji mountain are easy visual reference points. While a subtle tradition of hierarchical respect expressed in bows, hardwired rules paired with obedience, and a blurry/impenetrable understanding of the world are less popular trademarks of the Japanese way of life.

Beware of my lengthy story because I will tell you about everything.

Let's do some history real quick

But before going into detail, I will lay down some historical foundation for a bigger picture.

Year 1543 — the first Europeans who set their foot in Japan were two Portuguese traders, washed ashore after a shipwreck. They didn't know a word of the local language, so they communicated through gestures and symbols on the sand. One thing led to another, and in no time those two were already 'selling' Christianity and muskets (locals used swords) to the Japanese. A year later, Japan was actively producing those exotic weapons.

In 1549, a Jesuit missionary arrived with a dirty goal of converting the locals to their orthodox religion. Even though Japanese were moderate in their religious beliefs, Christianity was too demanding with its almighty God. It was a hazardous undertaking in the country where there was to be only one absolute – the sovereign. No wonder that soon after, Christianity and its followers were banned and punished by death penalty.

1639 was the year when a decree on shutting the country's borders was declared. In and out.

Year 1868— Meiji Restoration brought an official ending to the six-century military rule and isolation. The modernization took form of the Western technology adoption, industrialization, compulsory education, constitution + army. The national identity was in the making to unite the citizens.

1875 –1945 – a period of aggressive Japanese imperialism and war crimes.

2 September 1945— The surrender of Imperial Japan in WWII.

1946— A decree of the New Democratic Japan.

Till 1952— An American military occupation of Japan.

After the 1960s— the concept of the national identity was revised: superiority was replaced with the notion of uniqueness and authenticity. The economic boom made Japan the second largest economy.

Abide by the rules. Follow the traditions

Majority of those visiting Japan describe it as another planet. You feel it the moment you step out the plane and get acquainted with the locals' mentality. I would characterize it as an innate disposition towards being respectful and polite. Of course, there is a host of historical and cultural implications for such attitudes. A devotion to conventionalism and moderation can be found in many aspects of life. Like:

Job-for-life model is widely spread across the country. It's a tradition of starting and finishing (age-wise) your career path at the same company. After university, if you show enough commitment and hard work, you can be hired by a successful company. You will start as a lousy assistant, slowly moving up the career ladder over the course of your life. Or take families. Being shy, the Japanese tend to overcome their natural reserve somewhere around their thirties-forties. That's the age they usually get married, preferring to invest the power of youth into career.

Tradition and obedience are core, where everything has its own role, function and place. Proofs? Just observe Japanese queues: you will never see people hustling through the crowded streets because personal space and distance are sacred here. You can also notice lots of complex rules governing how to serve food (lots of separate dishes with assigned applications). Food is a sophisticated topic that I will return to later.

Even in ancient records, we already see the emphasis on following instructions from higher authorities or adhering to traditions is evident. In the 17th century, there's a recorded instance of an unfortunate daimyo (lord) losing both his land and life simply because he wore his pants incorrectly.

Now, let's talk about clothing. Nobody wears kimono on the streets nowadays; it has already migrated to the category of national costume. The good thing about kimono is that it's 'one-size-fits-all', that's why it's inherited like fine jewelry (with pretty much the same price range). Though women still wear this silky attire on very special occasions like weddings or ceremonies. Or like in the photo below, in a hotel room just for fun :)

Cruel echos from the past

Many are familiar with the dark chapter in Japanese history marked by atrocities and brutality during the age of imperialism. Apart from war crimes during their aggressive expansion into Asia, and WWII, Japanese soldiers were infamous for brutal killings of war prisoners, human experimentation (like cutting the womb of a pregnant woman to see how the baby develops inside), biological warfare, and even cannibalism. This disturbing behavior occurred in organized squads where prisoners had pieces of flesh cut from them, leading to slow and agonizing deaths.

The root cause? While I may not possess an in-depth understanding of Japanese history, it can be traced back to the tradition of a prolonged military rule that dominated the country from the 12th to the 19th century. The samurai, or warriors, were a military nobility class known for their code of honor, indifference to pain, and unflinching loyalty to their masters. So, samurai were the manifestation of bravery, fierceness, and cold-blooded determination unbound by nothing. This historical context sheds some light on the roots of the extreme actions during this period.

I want to explore the saying that suggests every Japanese is still a samurai at heart, and to illustrate this, I'll share an intriguing story from our local guide—a Russian residing in Japan for 15 years and married to a Japanese woman. So, he has plenty of cultural gossip to spill.

The story: his Japanese mother-in-law is a respected business lady and a head of a huge corporation. One time she went out for a fancy dinner and didn't like the service at the restaurant. She finished her meal and left without any signs of discontent. However, the following day, she handed money to a homeless individual with a peculiar request—to urinate on the doors of that restaurant every day for an entire month! Can you imagine that? What an elaborate vengeance (: he warrior's spirit still resonates in unexpected ways in contemporary Japanese culture.

Tiny (from my perspective, of course) objects are national hallmarks. My mum and and my hand for comparison.

Japanese values stay rock-solid even in the times when social norms are getting globally relaxed

Lots of values and traditions, still dear to the Japanese, are rooted in the Confucian ideas (based on respecting ancestors, doing no harm, and acting justly/morally) that came from China and become a system of strict social prescriptions. Japanese people were assigned a hereditary class based on their profession, which would be directly inherited by their children. Despite the fact that nowadays people are usually socially classified based on their socioeconomic status (education + occupation + income), the social mobility in Japan is a bit stiff compared to the Western world.

For example, it can be noticed in a job-for-life model, where a person chooses a particular career path and spends their life by improving a chosen professional skill. A breathtaking documentary about a Japanese 85-year-old (as of 2011) sushi chef Jiro Dreams of Sushi is a great illustration of that. Throughout his life, Jiro focused on one thing: mastering the art of sushi, transforming his modest eatery in a Tokyo subway into an internationally recognized establishment.

Moreover, the film touches on the strict rule of family succession: Jiro has two sons (each of them is a sushi chef). However, according to tradition, the eldest son must inherit the father's business, while the youngest is left to his own devices.

Submission to elders is part of the universal rule of respect for authority that has been present in the Japanese culture from the very beginning (submission to the sovereign is absolute and unconditional). The concept is so important that the Japanese language itself is honorific. Meaning there are different forms of speech to express respect, politeness, and humility that reflect the significance of hierarchy of being senior or junior. There are three types of honorific language: 1) Polite language, 2) Respectful language, and 3) Humble language, the choice of which depends on the rank and class of a person being addressed. This hierarchy goes beyond language and is also expressed in the culture of bows.

For that precise reason, handshakes didn't strike root in Japan apart from other Western trends like chairs and jeans. In this simple hand movement, there is no gradation of respect as opposed to a bow. The Japanese have different bows for different social contexts. It's hard to tell the status of a person at first glance unless you both bow to each other. By judging the angle of a bow one can identify the other's status.

Broadly speaking, the respect culture is embedded across all levels of society. School curriculum includes moral education as a compulsory subject for everyone. By the way, programming is also taught since the early years of pupils (awesome move)! The education system in Japan is generally progressive. They don't just teach you standard subjects. The system incorporates integrated studies that offer a holistic understanding of the world, covering themes such as international understanding, welfare, information, and the environment.

Tokyo, former Edo, is the seat of the Emperor of Japan

Japan, as you may have already noticed, is special in many ways, one being its remarkable development achieved without heavily relying on meat consumption. Considering that 67% of the territory is uninhabitable due to extensive mountains, that's quite a feat.

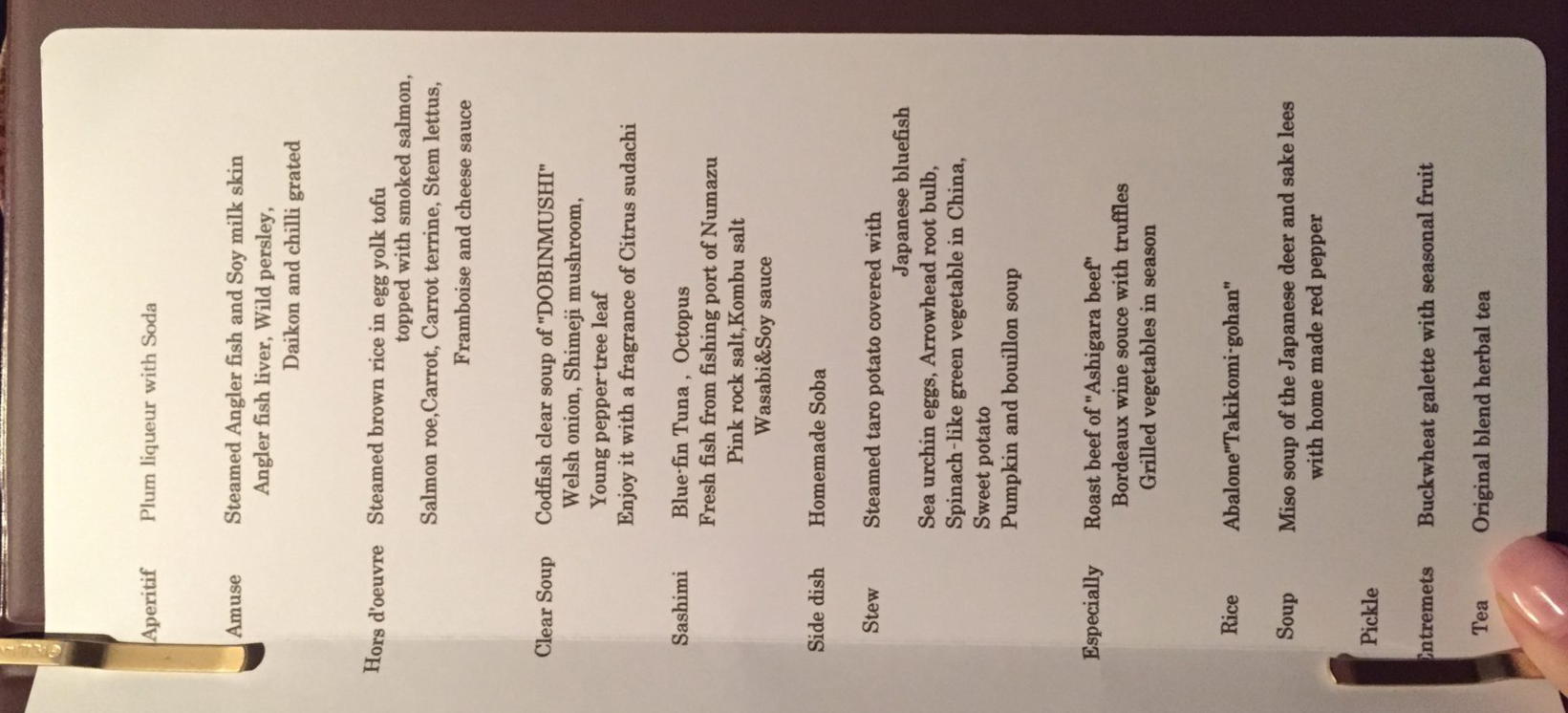

I'd like to focus on the Tokyo segment of this post to delve into the national food content because, interestingly, the former city of Edo became the birthplace of the fast-food industry in the 17th century. Edo created a vast network of cafes where people could quickly grab a bite or opt for takeaway, a concept familiar to us today.

The typical diet was modest and not that rich in flavour: tea, rice (eaten with chopsticks, borrowed from Chinese tradition), miso soup. As for meat, the locals didn't raise animals specifically for food, though the elite could indulge in wild fowl. FYI, eating meat was considered taboo in Japan for 1200 years, reinforced by the Emperor's order backed up by death penalty.

The first sushi were nothing that we know by this name today. It was a laborious way to preserve fish: it was peeled, sprinkled with salt, dried, stuffed with boiled rice, sprinkled with salt again, poured with water and left for at least a year. Fermented sushi was the result. And only at the beginning of the 19th century, edo-sushi was born – a bun of rice with a piece of fresh fish, molded by hand.

As for sweets, there weren't any until the unwelcome Portuguese guests who introduced sugar, caramel, candies, and wine to lure the Japanese with these delicacies and convert them to Christianity. What's more, they even brought new methods of cooking – before that, the locals hadn't utilized baking or frying. Bread? Also, an alien foodstuff that was 'mastered' in the 1870s. Though nowadays cakes aren't all the rage too. Steamed pastries with bean paste are probably the maximum you get out of sweet taste in Japan.

The 1st century banquets laid out the foundation of Japanese aesthetics

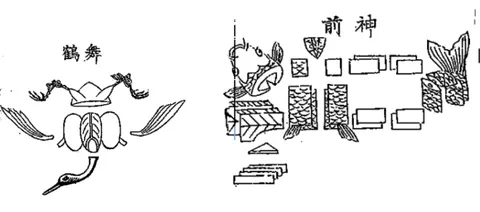

The aristocratic era in Japanese history begins in 710, when the first permanent capital was founded in Nara. The imperial banquets of the early Heian period are not distinguished by their splendor: they consisted of pyramids of colorful rice, decorated with millet, and a few rather simple dishes. However, it was at this time that the foundations of Japanese aesthetics were laid which will remain practically unchanged to this day.

During this period, the courtiers and aristocrats of that time – no more than 20 thousand people throughout the country – learned to value qualities such as simplicity, elegance, sophistication, and understatement, as opposed to the splendor and abundance that the imperial court lacked.

The bureaucrat, prince, and warrior were expected to appreciate the play on words, compose short tanka poems, and decipher allusions to poetic and literary plots found in bouquets of flowers, fabric patterns, and fruit combinations on trays. Failure to recognize the flower encoded in a poem could even lead to suicide.

Can you see the connection between the early banquets and Japanese aesthetics? Here are the aspects of it:

- Emphasis on Simplicity and Elegance

The banquets during the 1st century, particularly in the early Heian period, laid the foundation for valuing simplicity and subtlety. - Symbolism in Culinary Arts

The banquets introduced the concept that everything on the plate had symbolic meaning, with the meticulous arrangement of food items, colors, and ingredients choices conveyed deeper messages. - Integration of Arts

The ability to recognize and interpret poetic allusions in flower arrangements, fabric patterns, and fruit combinations demonstrated a holistic understanding of the arts. - Cultural Literacy and Etiquette

The aristocracy of the time cultivated cultural literacy, including composition of concise tanka poems, discernment of subtle art references, and an appreciation for the significance of every detail in the banquet setting. - Philosophy of Understatement

Instead of overt displays of wealth, the focus was on the subtle and the restrained, a philosophy of understatement that is evident in various aspects of Japanese aesthetics, from tea ceremonies to traditional architecture. - Connection to Nature

The appreciation of seasonal changes and the use of natural motifs are integral components of Japanese artistic expression.

Kyoto is the cultural capital and it shows

Now I want to show you the ins and outs of Kyoto through Geisha culture and Zen Buddhism —integral cultural aspects of Japanese heritage that find their rightful place here.

The thing that annoys me about the concept of geisha is that it's absent in the Western world. Because of that, geishas are tainted by an inaccurate stereotype, wrongly associating them with prostitution. In reality, those women are trained performance artists and entertainers that attend parties of of affluent men. Geisha has a distinctive look, characterized by an elegant kimono, intricate white powder makeup, and a traditional hairstyle.

At 17, girls willing to master the profession should submit for apprenticeships in designated tea houses. They learn skills of music, dancing, singing, and communication by observing their experienced peers. To some modern Japanese feminists, the act of teaching women to entertain and flirt with men seems humiliating. Yet, geisha describe their profession as completely opposite to that. In earlier times, when women had limited rights and were often confined to roles as mothers and wives, being a geisha was considered liberating, offering an escape from traditional family obligations.

Today, a few geisha are assigned the status of "living national treasures", the highest artistic honor granted by the Japanese government. This recognition preserves the intangible cultural heritage, with each laureate receiving an annual award of 2 million yen for their exceptional artistic talent. I hope it dispelled some of the misguided and negative perceptions about geisha.

Japanese Zen gardens

While Buddhism is widely known, Zen, more of a school of thought, serves as a uniques addition to the religion. The essence of Zen Buddhism lies in directly understanding the meaning of life through insight rather than logical thought. Achieving this intense insight involves connecting with nature and one's own essence, usually with meditation and guidance from a teacher.

In cultivating the right state of mind, teachers use koans—questions without clear answers. One of such koans is this: "Two hands clap and there is a sound, what is the sound of one hand?" The purpose is to guide the mind in breaking through dualities, categorizations, and divisions, giving way to a deeper understanding of the interconnected nature of all things.

To help one delve into the mastery of Zen, there are Zen gardens, a uniquely Japanese twist on the arrangement gravel and stones that mirrors the subtle essence of nature. Contemplating such landscapes facilitates immerses you into meditation, guiding the mind toward a detached state of nothingness. Unfortunately, fully immersing oneself in this experience is challenging due to the constant influx of tourists, much like myself, in Kyoto's oldest Zen garden. Nevertheless, the atmosphere remains undeniably majestic.

There are lots of deers in Nara

Deer, considered somewhat sacred, will bump into you for treats with no shame (another uniquely Japanese experience). These endearing yet bold creatures are wandering among numerous Buddhist and Shinto shrines. By the way, Shinto is the largest Japanese religion following Buddhism.

Its allure lies in its simplicity and decentralized nature. No chief gods, stringent rules, moral regulations, sacred texts, or icons. Shinto centers around kami —supernatural spirits living in everything. Here, faith is paramount; believing that your cherished stone helped in securing a dream job allows you to venerate it as your personal kami. Simple and delightful, that's Shinto.

Fascination for things

I looked at what I wrote. And well… Lots of information, I know. I couldn't resist the charm of the Japanese culture. Allow me to conclude with an exploration of the art of capturing the fleeting essence of existence—a realm perpetually slipping away from being defined by language.

Locals capture this indescribable phenomenon with the term "shibumi" (渋み). It embodies a unique and elusive sense of beauty, associated with the puckering tartness found in persimmons. When contemplating shibumi, the taste that comes to mind is that of green tea. Despite its elusive nature, this feeling effortlessly surfaces, conveying a blend of tart bitterness, simplicity, a rejection of superficial beauty, raw form, and innate imperfection.

Haiku – a Japanese short-form poetry, achieves a distilled representation of reality through its three concise lines, offering a glimpse into the poet's insight. It goes beyond mere description; the classics tell us that haiku is about naming things, using raw and simple words as if calling them forth for the first time.

Have a read of those two Matsuo Bashō poems:

- Why so scrawny, cat? /Starving for fat fish or mice… /Or backyard love?

- Ah spring spring / How great is spring! / And so on